4.5/5

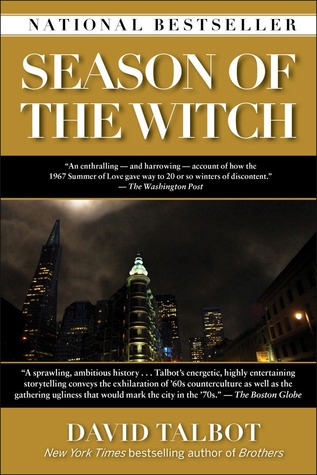

4.5/5Simply fascinating! I've lived in San Francisco for the better part of the last 20 years, but there is so much I didn't know about my adopted hometown. In newsy, easily digestible chapters, Talbot takes readers on an intimate tour of the highs and lows of Baghdad by the Bay, from the first blush of the Summer of Love to the invention of the cocktail that saved countless suffering HIV patients from certain death. (FYI, while those events make neat emotional bookends, Talbot also covers some earlier socio-political history, mainly to set the context for the revolutionary times that are his focus.) Maybe most importantly, Season of the Witch (named after the Donovan song) sheds new light on just how those now-infamous "San Francisco values" came into being.

For his book, Talbot interviewed many well-known but disparate locals, including former Mayor, now Senator Dianne Feinstein, writer Armisted Maupin, Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart, and cult survivor Jim Jones, Jr. But he also took the time to talk to lesser-known game-changers like David Smith, founder of the revolutionary Haight Ashbury Free Clinic, and Dr. Paul Volberding, an early hero in the field of AIDS research. Both medical men have harrowing, yet ultimately heartening stories to tell. Talbot also profiles countless other San Franciscans from all walks: black music promoter and patron of the Fillmore district, Charles Sullivan, who gave Bill Graham his first big break by "loaning" him the Fillmore Ballroom on unbooked nights; legendary 49ers coach Bill Walsh, who took the team (and the City) to glory in the 80s; beloved society columnist Herb Caen; and of course liberal political and gay rights martyrs George Moscone and Harvey Milk.

Just like San Francisco weather, the light moments here are interspersed with the dark. The Diggers confound shoplifters with their Haight Ashbury Free Store. Control freak Bill Graham gets dosed at a Grateful Dead show. Mayor Moscone and future Mayor Willie Brown paint the town red. The Cockettes and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence raise eyebrows while raising funds for local causes. The 49ers bring the City back from the edge of despair with a near-miraculous Super Bowl victory. And also: hordes of sick and malnourished flower children live in conditions comparable to Calcutta; the Altamont music festival spirals into a mess of blood and blame; heiress Patty Hearst is kidnapped by the shadowy SLA; and the Zodiac and Zebra killers run amok simultaneously, with a minimum total of 30 victims between them.

But the centerpiece of the book is when Talbot relates, in graphic detail, the two bleakest moments in San Francisco history since the 1906 quake and fire nearly wiped it out: in November 1978, popular Bay Area based preacher Jim Jones led 918 Peoples Temple followers to "revolutionary suicide" in Guyana -- leaving thousands of friends and families bereft. The liberal civic leaders who had been Jones' boosters were mortified. Then, just nine days later, Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk (both still reeling with shock and horror about their association with Jones) were assassinated in their City Hall offices by disgruntled former Supervisor Dan White. Dark days indeed.

I have one small reservation, based on purely personal bias. Nearing the end of his tale, Talbot includes two whole chapters on the birth of the championship-era 49ers (including some play-by-play of the 1982 Superbowl), but only one on the whole arc of the AIDS epidemic. I suppose if you like football that's a treat, but to focus on the struggles of a football team -- even one that may just have saved the morale of this city -- and yet give admittedly moving, but very short shrift to the thousands who died horribly before medicine caught up with liberation seems somehow wrong. But hey, maybe that's just me and my crazy San Francisco values. In the end, Season of the Witch makes for one fascinating true tall tale. 4.5 stars.